From Traumatic Brain Injury to Musical Revelation

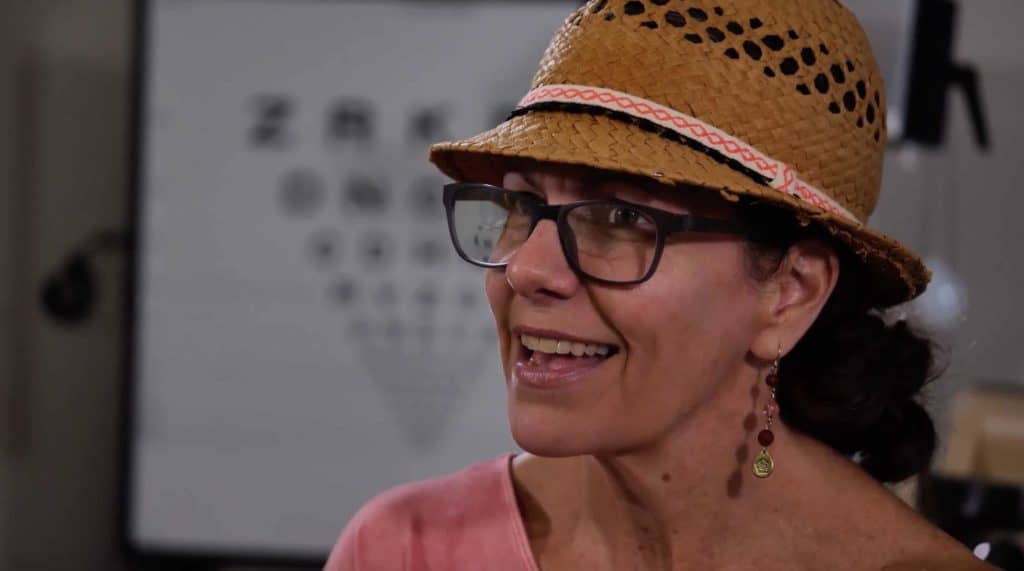

Her former math proficiency may still remain “rough,” but Meg Scrivner, mother of four, is not too worried about numbers right now. That’s because she is singing in a band and writing songs at the piano – new talents she believes she owes to a brain injury, testing at the Mind-Eye Institute and several pairs of therapeutic eyeglasses.

“A piano teacher once told me I would never learn to play the instrument; I did not have the talent. But after getting my prescription glasses, I started hearing music in my head. So, I sat down at the piano [to write]. Now, I have a book full of songs,” says Meg, a girls’ gymnastics coach, who continues teaching in her hometown of Andover, Kansas. “Music seems to have filled the void in my brain once occupied by my math abilities.”

Of course, learning piano was not the reason Meg made her first appointment at the Mind-Eye Institute in Northbrook, Ill.

The Car Accident and the Symptoms that Followed

Rewind to 2015 when the vehicle that Meg is driving — two daughters, ages 11 and 15, riding with her — is broadsided. She sustains a traumatic brain injury, which hinders her ability to process information or read and highly sensitizes her to sound and light. Her daughters also are hurt in the collision.

“I could neither hear correctly nor tolerate light following my injury. I had to wear a hat outdoors, and, indoors, my husband and I put up curtains to go over blinds and used low-wattage lighting,” Meg relates. “My speech deteriorated. I had only a first- or second-grade vocabulary. I just couldn’t think straight. I stumbled; bumped into things. I could not even read signs while driving. And, I experienced horrible headaches.”

As a result of her head injury, Meg was diagnosed as having symptoms of post-traumatic stress syndrome (PTSD), but the health care practitioners she saw in the Andover and Wichita, Kansas area proved of little help in mitigating her symptoms.

Equally dissatisfying was Meg’s visit to a couple of concussion specialists, one of them a neurologist “who just wanted to give me meds for depression.

“My general physician tells me to do nothing, rest, stay in bed,” but that proved to be the wrong advice, Meg says. Equally dissatisfying was Meg’s visit to a couple of concussion specialists, one of them a neurologist “who just wanted to give me meds for depression. I said, ‘I am not depressed. I need to be functioning, not muddling my brain.’

“The more I learned about my condition, the more I realized how I had to find a practitioner who knew about treatment of brain injury,” she says.

"The Ghost in My Brain" and Search for the Mind-Eye Institute

Instead of remaining at home, Meg engaged in activities to challenge her brain, including a return to a coaching position at the Andover public-school system.

“I was no longer able to coach higher-level gymnastics but was able to compensate enough to work with another instructor in teaching younger girls,” she says. “And, every night I read to try improving my comprehension, retention and vocabulary.”

Her condition improved – “a little” – during a 14-month span, but Meg continued struggling with everyday tasks. Then came a fateful trip to the local public library where a recently published book, The Ghost in My Brain: How a Concussion Stole My Life and How the New Science of Brain Plasticity Helped Me Get It Back, caught her eye.

In it, DePaul University academician, Dr. Clark Elliott, details his two-year journey back to health following eight years of symptoms from mild traumatic brain injury. He calls the work of the Mind-Eye Institute “magic” and credits his recovery to its founder and research director, Deborah Zelinsky, OD, as well as to neuroscientist Donalee Markus, PhD of Designs for Strong Minds™.

An internationally recognized expert in the field of neuro-optometric rehabilitation, Dr. Zelinsky has revolutionized scientific understanding of how eyes and ears are linked via the retina, which serves as a two-way portal between body functions and environmental stimuli.

With the assistance of her husband, Meg read the Clark Elliott book and took the plunge – she contacted the Mind-Eye Institute for an appointment.

The rest is history.

The First Visit and First Pair of Therapeutic Eyeglasses from the Mind-Eye Institute

“I underwent extensive testing during my first visit to the Institute. I recall Dr. Zelinsky telling me that my head injury had changed my environment and that she would help me resynchronize and rebalance my sensory systems,” Meg says.

“The right mix of filters, lenses and/or prisms can readjust a patient’s visual balance and eye-ear connections by altering the way light disperses across the retina,” Dr. Zelinsky explains. “Mind-Eye ‘brainwear’ glasses selectively stimulate light on the retina to help patients redevelop visual skills during recovery from debilitating, life-altering symptoms of brain injuries or to support development of new skills in patients with learning problems.

“Our eyeglass prescriptions are designed for sensory integration, bringing patients like Meg relief for a range of symptoms caused by eye-ear imbalances, brain injuries and other neurological issues.”

-Dr. Deborah Zelinsky, OD, FNORA, FCOVD

Meg remembers wearing her first pair of therapeutic glasses from the Mind-Eye Institute.

“At the time, I did not realize what a change my new glasses were making. The other teacher with whom I was coaching gymnastics also happens to be a speech pathologist. We had divided the girls into groups, and I started giving directions to my students. The pathologist was astounded. She said, ‘You have just given concise, specific directions that everybody understands. You haven’t been able to do that.’ It was then she realized I was wearing my new glasses.”

Meg's Continued Brain Injury Recovery

Meg recently “graduated” to her fifth pair of prescribed eyeglasses from the Mind-Eye Institute and says she is feeling “like I am almost back to my full personality. My math remains a little rough, but I can do my checkbook.” She also continues reading every night in an effort to replace what she calls “some missing pages in my brain dictionary.”

Meg says, “the Mind-Eye Institute has changed my life.”

Back to the piano.

Meg’s emergence as singer and song writer may be due, in large part, to the effects of the Mind-Eye’s therapeutic glasses, which are helping forge new informational pathways around damaged brain tissue and potentially stimulating untapped regions of the brain.

Indeed, there could be a whole new, unexplored world inside our heads. Just ask Meg.