Recent study results suggest depression can cause imbalances in a person’s processing of the “internal mental world and external world” and seem to underscore the Mind-Eye Institute’s longtime application of therapeutic, individualized eyeglasses to bring symptomatic relief to patients with injuries and mental disorders affecting visual processing.

Authors of the study, published in a 2021 edition of Clinical EEG and Neuroscience, conclude that depression may take a person’s attention away from “external signal processing” and lead to over-emphasis of the internal world (internalizing), “with potential consequences in various cognitive domains [of the brain]. Extensive control of the internal emotional and cognitive world” often results in an internal expression of distress, and “is a common feature of internalizing disorders [such as depression].”

Deborah Zelinsky, OD, concurs. In fact, as founder and executive research director of the Northbrook, Ill.-based Mind-Eye Institute, Dr. Zelinsky was invited to address scientists, physicians, and engineers gathered at the 2018 N20 World Brain Mapping & Therapeutic Scientific Summit in Argentina. There, she spoke on how mental health disorders, including depression, can be as much related to retinal sensitivities in peripheral eyesight and lack of integration between sight and hearing as they are to abnormal brain activity and neurochemical imbalances. At that N20 consortium, policies were written to give to the G20 leaders, who were also meeting in Buenos Aires. Dr. Zelinsky’s contribution was that eye screenings needed to be updated to include how people visualized auditory space.

“Just as changes in environmental stimuli can impact brain function and chemistry, so, too, eyeglasses can stimulate the retina, helping symptoms caused by neurological issues,” she told summit participants. Dr. Zelinsky is world-renowned for her knowledge of how to influence retinal function using successful clinical applications of advanced optometric science.

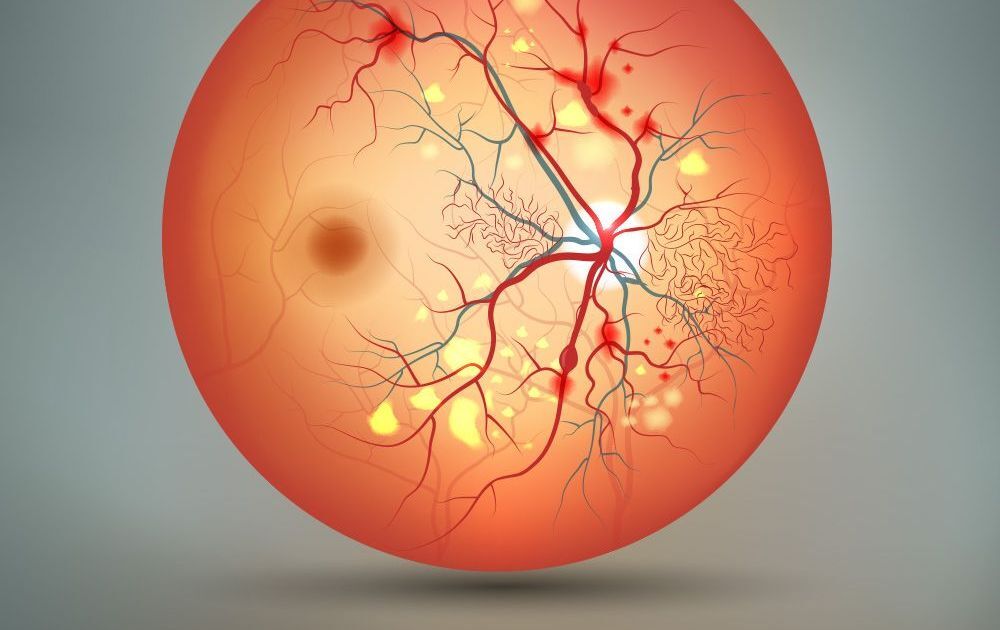

“The retina is a bi-directional neural interface and an actual part of the central nervous system. Since retinal signals are processed by many regions of the brain – not just the visual cortex, the implication is that retinal stimulation [through variances in light] can affect other physiological processes, including motor control and biochemical activity,” she states in a recent paper on Neuromodulation Via Retinal Stimulation.

“Because of the retina’s critical role in brain function, therapeutic [brain] eyeglasses…may be used in patients who present with a range of physical and mental health disorders. Individualized lenses can change the dynamic relationship between the mind’s visual inputs and the body’s internal responses by altering spatial and temporal distribution of light on the retina. The novel use of light to affect the nervous system has already been successfully applied to a range of disorders, including jaundice, jet lag, seasonal affective disorder, brain trauma, and spinal cord injury. Indeed, optometrists can use light to regulate both a patient’s physiology and behavior,” she writes.

Citing the intricate links between the brain retinal function, Dr. Zelinsky says she is not surprised that the depression study offers additional insight into how neurological disorders can “throw off” normal synchronization between a person’s attention to internal stimuli and his/her processing of information coming from the outside world.

“Intact visual processing skills are essential to all aspects of quality life,” Dr. Zelinsky emphasizes. “If central and peripheral eyesight fail to connect and interact properly or if eyesight and listening abilities are uncoordinated, then a patient’s ability to visualize is affected.”

The term “visual processing” refers to the brain’s almost-instantaneous ability – consciously and non-consciously – to take in external sensory signals (from eyesight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch), combine them with a person’s internal sensory signals (such as head position and muscle tension) and then synthesize – process — the information, allowing a person to react and respond normally to his or her environment.

“People can become confused about their surrounding environment, have limited perception and awareness, and experience difficulties in learning, attention, reading, cognition, posture, and balance when brain circuitry is not synchronized,” Dr. Zelinsky says.

She uses post-traumatic disorder (PTSD) as an example of visual processing gone askew.

“The central nervous system’s – and by association, the retina’s — processing of feedback signals from the body regulates emotions, including fear. If this body-brain interaction becomes muddled by injury or neurological disorders like depression, a person can go into chronic fight-or-flight mode, experiencing panic attacks, anxiety, and even post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

PTSD often keeps a patient’s mind and body systems in a hypersensitized “fight-or-flight” condition. Common PTSD symptoms include changes in perception and decision-making, which, in turn, cause abnormal reactions to the environment. Awareness and attention are affected. A person with PTSD suffers from spatial dysfunction and disorientation. His or her visual world constricts because peripheral sight becomes either hypersensitized or, as in depression, turned off. The patient fails to pick up all surrounding environmental cues, expends more mental and physical energy to make “sense of everything,” becomes “wiped out,” and eventually finds it easier to “tune out.”

“The struggle to understand the environment can lead to – or sustain and deepen – depression, along with irritability, outbursts of anger, irrational behavior, and sleep problems. Biochemical changes also occur in response to disruptions in awareness,” says Dr. Zelinsky, adding the Mind-Eye Institute does not treat PTSD. “However, we are often able to lessen visual stress. The lowered level of overall stress can sometimes make the PTSD symptoms bearable.”

As Mind-Eye optometrists, “we are continuing to push the boundaries of our understanding of the interaction of retinal signaling with brain functions,” Dr. Zelinsky adds. “We are grateful for the ongoing work of researchers in this area and look forward to future collaborations.”

image from Eye Physicians and Surgeons, P.A.